Yesterday at dinner, the three-year-old I was babysitting speared a piece of chicken with his bulldozer fork and asked me, “What’s this?”

He knew it was chicken, having moments before squealed with delight at the breaded cutlet I had pulled from the fridge and plopped before him, “Ooh! Chick-fil-A!” But I took up my part in the near constant patter we maintain.

“It’s chicken,” I said.

“Where chicken come from?” he fired back.

“You know, the animal. Chicken. Like on your farm puzzle?”

“Why?” he said.

Like most little kids, Nicky is a natural teleologist with a near limitless capacity for posing this simple syllable. I generally take a stab at entertaining both of us with a good faith answer, attempting to peel back the layers of causality to whatever he’s boring into with language accessible to a toddler. It inevitably ends with me backed into an existential corner, musing back at him, “yeah, why is that?” with a stumped look on my face, or simply repeating, “I don’t know, Nicky,” until the line of inquiry finally loses its hold.

I recently overheard him explain to his baby sister that he was putting a stray sock back into the drawer so “it could be with its family,” the same why I’d offered him to explain my policy of throwing box elder beetles out the back door into the yard rather than smooshing them on sight in the basement. Sure, the infinite why game is an easy way for a hyper-verbal kid to engage a willing adult, but I realized with a shock of delight and responsibility that he was actually processing at least some of my responses.

The primary task of care-taking children is of course to make sure they survive to adulthood, a mission that encompasses everything from fishing unidentified floor findings from the baby’s mouth to fleeing the family home as bombs fall from the sky. But the secondary task, to shape what kind of adults they become, is just as vital to our collective survival.

As kids, we learn the rules of this incarnation by constant testing and exploring, our fluid experience of reality solidifying into the architecture of the culture around us. The values of that culture, which we depend on for our survival, are refracted through our inner belief systems, into our own language and behavior. And through this generational reverberation, greed, disposability, and violence have been reinforced as the dominant memes of our time.

I witness most millennial parents attempting to break these cycles, raising their kids with a transparency and autonomy that many of us were not afforded growing up. My friends talk to their kids about drugs and alcohol without sensationalism, they demystify sex, apologize when they make mistakes, encourage questions with non-judgment. I’m so proud of them. They want to be someone their kids can trust, not someone they fear. Hell, a lot of them decided to not even deceive their kids by selling the story that a real man with a sweet tooth climbs down their chimney loaded with presents made by elves.

My instinct with kids – with anyone, really – is to tell the truth. I’m not much good at lying these days. I don’t have the taste for it anymore. But I won’t throw the truth at you and run away. If it’s a hard truth, a scary or uncomfortable truth, I promise we’ll look at it together. So when Nicky held up his chicken bite and asked me “why,” I searched for what is true and what is kind.

Most American kids are not raised to connect the adorable animals in their storybooks to the food on their plate. When I was around five years old, my mom’s dinner rotation included “bunny dogs,” hotdogs we often requested with a side of baked beans, until one day I had the horrific revelation that bunny dogs were, in fact, made out of rabbit meat. I remember my mom laughing with surprise. We called them bunny dogs for Pete's sake. It wasn’t a secret. But the idea of killing rabbits – bunnies! – for dinner was so unconscionable, it hadn’t crossed my mind that the name was explicit. So what are the chances a child will link the barnyard animals cow and pig to the beef and pork on their plate? Chicken to nugget?

A recent study published by the journal of Environmental Psychology found that 40% of kids ages 4-7 think hotdogs and bacon come from plants.1 But this shouldn’t really be surprising. Look at the grown ups. For most of us, the basic concept of necessary slaughter – let alone the unnecessary horrors of industrialized farming – is so uncomfortable that we’ve settled on willful ignorance, stuffing our fingers into our ears: I love animals, and I also want to eat meat, la la la la la.

This so-called “meat paradox”2 allows us to compartmentalize the massive scale of suffering inherent to our modern foodways, while exorcizing our grief and outrage on people who raise pit bulls for dogfighting and toss unwanted kittens into roadside ditches. The world is overrun with violence and there is so much to be sad about. Just keep the steps between chicken and Chick-n-Strip invisible and give the family dog the best 13 years possible.

But I don’t think that’s fair. To kids. Because that study also found that more than 70% of those same 4 to 7-year-olds identified pictures of cows and pigs as “Not OK” to eat. What in Santa Claus gaslight hell is this?

My granola-baking, no cable TV-watching mom was cooking me dinner in Portland, Oregon in the early ‘90s, and I have no doubt that she sourced local, small-batch bunny dogs of the sort that are hard to find these days. If you’re going to eat meat, rabbits who lived the good life munching clover on an actual farm are a pretty solid choice. But none of this mattered to me. I felt betrayed. If the origin of the bunny dogs had been clear to me, I would never have eaten them. And we never did again. My mom respected the moral impasse.

Evidently the majority of kids carry an innate sense of relation to their fellow incarnates. If the Environmental Psychology surveyors had presented them with pictures of gestation crates and debeaking machines, what percentage would select “Not OK”?

“Very Bad”?

“I Want No Part In This, Get Me Out Of Here”?

Why not let kids express the obvious? What might we learn from their clarity? Are we so afraid of the karmic responsibility of our own dinner plates that we cannot let them name what is true?

***

"I refuse to lie to children. I refuse to cater to the bullshit of innocence” the author Maurice Sendak gleefully avowed.3 His books, notoriously lush with peril and nakedness, were a balm to me as a child. As I got older, Sharon Creech, Susan Cooper, Mildred D. Taylor, Madeleine L’Engle – they all respected me. They didn’t try to sell me the lie of a safe world, where men always do the right thing and mothers never die.

Welcome, kiddo. I know you see what’s going on here, they said. Bad things happen and the people we love will die. But you have agency, because you have a heart, and anyone who says you don’t because you're just a kid is afraid of your power.

I did know what was going on. All kids do. We hear the arguments through the walls, we see hungry people sleeping on sidewalks, we are hurt by adults who are supposed to take care of us. These authors gave me permission to relinquish the performance of innocence. Together, we bore the sorrow and the beauty of the world, and they prepared me for the real life stories that soon obsessed me: the Holocaust, American slavery, news coverage of kids my age getting sniped on their way to school in Sarajevo or working 16 hours a day stitching sneakers in Nike’s Cambodian sweatshops. I was ravenous. I needed to know. I needed to know what humans were capable of doing to each other. What was this world, really, that I was a part of? And why wasn’t everyone screaming from the rooftops, “Not OK”?

Lying awake at night in my childhood bedroom, the yawning darkness lapping at the edges of my bed, I struggled to hold onto the big, slippery knowing that everyone else alive in the world felt that they were the main character of life, just like me. They peered out of the eye holes in the container of their being and thought that life was their movie. Everyone else, passing in cars and walking down grocery store aisles, more people on the earth than my mind could stretch to imagine, inside all of them, their thoughts and worries and ideas were as big and real as mine. And though I could try to get close through books and stories, it was impossible to know what it was like inside any of them. I had to trust that they were just like me, with a different set of variables, different body, different family, different corner of the earth. It was a haunting, lonely, reverent feeling like looking up at the stars or into the ocean.

As I made my way toward adulthood and took on the business of surviving, the voice of my innate knowing was slowly subsumed by the narratives of institutions, the preoccupation of being somebody doing something in the world, and the fear of being trampled and left behind by a culture that clearly had no patience for anyone who questioned authority, made mistakes, got sick, or old, or tired. What you see is what you get, I learned. Ants have no self-awareness and fish don’t feel pain. Unethical consumption is exhausting and you need your strength to keep up. Put your head down, get on with it, and catch a dopamine rush wherever you can.

My world gradually became gray, flattened by logic and materialism. My innate sense of justice still raged within me, my system in a constant state of agitation, but with no spiritual allies and the steps to manifesting a life that made sense increasingly unclear, the only thing the fire burned was me. I moved to New York City at 18, placing myself in the center of a roiling energetic vortex big enough to drown out the one inside of me. I slid in and out of bars, guzzling down gin and tonics and the attention of older men whose hunger for me could temporarily replace my insecurities. I smoked weed on the sidewalk and inside private karaoke rooms, but my breezy lack of concern for the rules was tame and self-serving – I wasn’t threatening anyone’s power.

I spent years like that, running away from the small voice of mystery within me that more and more urgently tried to direct my attention to the truth that I was, in fact, Not OK.

***

In the introduction to Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy’s translation of Rilke’s Book of Hours, they write of the poet: “Rilke never lost his conviction in the bitter reality of the world. Or in our human capacity to redeem it through that act of transforming attention, which is naming – or love.”4

Our desire to insulate our children from the world mirrors our desire to insulate ourselves from the complicity of its suffering. Our grief, we fear, may drown us if we name it. But it is a tender irony that by closing down around our broken hearts, we suffocate the very thing that offers us redemption: our great capacity to love.

There is both exuberance and pain in the holy remembrance that the world is us – clothed in other bodies that take the shape of humans, of animals, plants, and the land itself. Hallelujah, we are part of a great mystery! But oh, my heart, look at the infinite ways we beings suffer in this realm, the many ways to die!

To hold this blaze of awareness without being burned by it takes muscle, the practice of building a capacious heart that every spiritual tradition in the world encourages us to undertake. But we are built for it. The more we do it, the more we realize how capable we really are. It is only when we are alienated from this power that we find ourselves curdled around a loss we do not know how to name. We call it depression or anxiety or addiction, and we continue to push away our connection to the world in the hope its sentience and suffering will ask nothing of us.

I hold close the belief that this has not always been our predicament. That in other stretches of human time, the memes of collective care and balance between give and take, consume and create, were woven through the fabric of human culture, held in place by rituals and stories passed between generations. Remember, remember, this is important, we told one another. Life is a ceremony.

My friend Oso, who grew up among the Lakota, told me a story once about a long hard year when food was scarce and his community was starving. It was a long drive to the reservation grocery store, and few had the money to buy gas or the processed goods on the shelves there. One day, a moose, he said, a rare sight in South Dakota, walked in from the hills and right down the street to his pickup truck. And then, it stood still. Oso ran to get his rifle and when he returned, a crowd beginning to gather, the moose was waiting.

“It stood right up next to the tailgate,” Oso said, “so when it fell, it collapsed into the truck. You know how much a moose weighs? It saved us a lot of work.”

In the most conscientious way, the moose willingly offered itself to people who would use every muscle, organ, sinew, and bone of its body to sustain themselves. To Oso, this was just another anecdote from the past. But to me, a product of colonialism, it was a magical story that warmed an ember of mythic possibility in my heart.

I see that ember now burning in the kids who are demanding our attention on campuses across the country. They are ablaze with the conviction of their truth-telling, invoking our collective powers of transformation. They carry the remembrance that we haven’t always been like this and that we don’t have to be now.

Their generation was impossible to shelter for long. Viewed from the internet, the world they’ve inherited was never a fairytale. They have seen the bloodied babies, the disembodied limbs scattered among piles of rubble, the mothers rocking shrouded forms that were once their children. They have seen the garbage mountains made of plastics that will never erode, the waters flowing through every tributary on earth poisoned with chemicals that will never degrade. Hundreds of thousands of species have gone extinct in their lifetime. Their friends are dying in record numbers from overdoses and suicides.

These kids have looked upon the world, and they have seen it as it truly is. Their hearts are breaking, and yet they will not look away. They are deep in the ceremony of love and grief, reminding us who we are. Not OK. Not OK. Not OK.

***

I look at Nicky. He is three. He loves fried chicken.

“Why?” he wants to know.

“Well,” I say. “That bite came from the body of a chicken. Once it was alive and now it is meat that you are eating to make your body strong.”

He is satisfied momentarily, chewing. Then he stabs a piece of fruit and holds it up to me.

“Where grapes come from?” he asks.

Read the complete study

The essential Maurice Sendak interview on The Believer

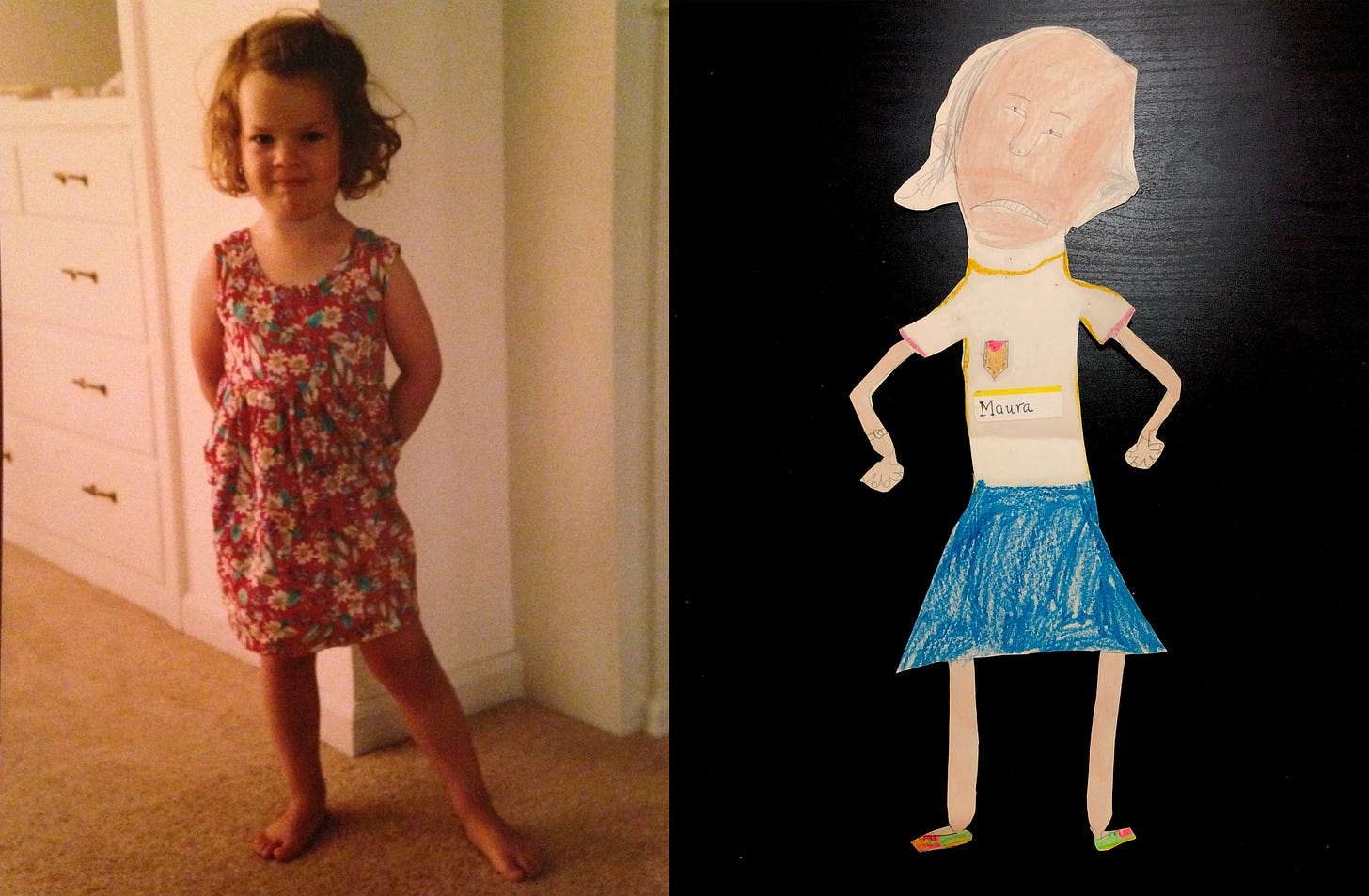

A spectacular, insightful & important essay on so many matters of great importance. Welcome to Substack, Maura! I cannot wait to read more from you, dear one.